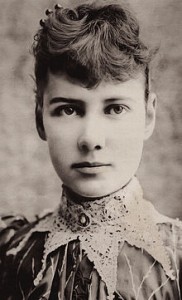

Part One: The creation of Nellie Bly, Reporter

*This post is part of an ongoing spotlight biography on Nellie Bly, who is often credited with the creation of the first steel drum*

Born the third child of her father’s second wife, Elizabeth Cochran joined a wealthy prominent family of Pennsylvania in May of 1864. She was considered the most rebellious of Judge Cochran’s offspring, and was lovingly referred to as Pinky by her family. Unfortunately, at age six, Cochran lost her father, and the family was later forced to auction their mansion home. They fell into hard times and Cochran’s mother re-married another man, for financial security, who was a drunk and often abused the family.

Cochran stood up for her family and testified in court against her step-father. Her step-father’s abuse helped shape her desire for independence and at age 15 she went to school to become a teacher. Money was still too tight, and Cochran had to leave school and move to Pittsburgh with her mother where she helped run a boarding house.

Cochran had distant dreams of being a writer, but it wasn’t until a popular Pittsburgh columnist pen-named “Quiet Observer” wrote that women belonged in the home cooking, sewing, and raising children. He went on the say any woman working outside the home was “a monstrosity.” Thinking of all the woman she knew working in industrial Pittsburgh in order to survive, Cochran wrote an angry letter to the newspaper. Impressed with her writing, the newspaper hired Cochran and gave her the pen name ‘Nellie Bly.’

While at the newspaper, Bly wrote articles about the difficulties of poor working woman, calling for divorce law reformation, and did a series about factory girls in Pittsburgh. Regardless of her investigative tendencies, Bly was continually given stories about flowers and fashion to appear in the women’s section of the paper. When she had finally had enough, Bly left her boss a simple note:

“Dear Q.O, I’m off for New York. Look out for me. Bly.”

After six months of knocking on office doors, Bly found a job at Joseph Pulitzer’s “New York World” under the supervision of John Cockerill. Her first assigned story in New York was to write about the mentally ill housed at a larger institution in the city. She faked a sickness to gain entrance and came back 10 days later. Her story told of horrible conditions, beatings of patients, and meals that were served with rancid butter. The story stirred the public and politicians alike, which brought money and much needed reforms to the institution. By 23, Bly had started a new kind of undercover, investigative journalism that her peers referred to as ‘stunt reporting.’

Join us next month for the second installment of “Nellie Bly: Woman of Steel”